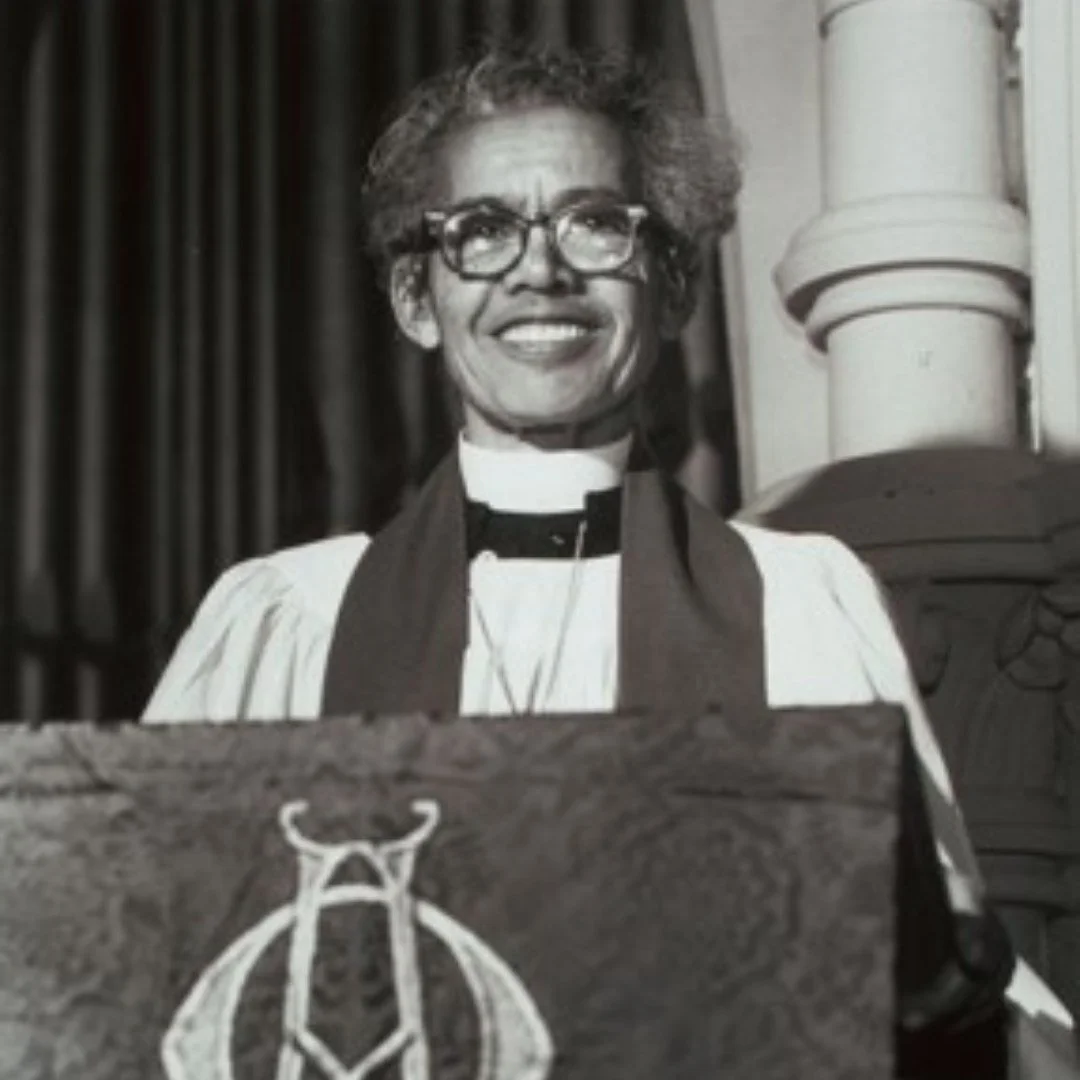

Barbara Lau recently interviewed the Rev. Winnie Varghese, who is giving a sermon at the annual Diocesan observance of the Feast of the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray. To learn more about the service, which will be held on June 22, 2022, visit this page on our website.

This interview was edited for length.

A national leader in the Episcopal Church, the Rev. Winnie Varghese is known for her inspired writing, teaching, and preaching. Before becoming the 23rd rector of St. Luke's, she served as Priest for Ministry and Program Coordination at Trinity Church Wall Street in New York City.

Prior to Trinity, Winnie served as Rector and Priest-in-Charge at St. Mark’s in the Bowery in New York. Winnie was also Chaplain at both Columbia University and University of California Los Angeles. She is a native of Dallas, Texas and is married to Elizabeth Toledo, a public relations executive. They have two grown children.

Winnie serves on the Board of Trustees of Union Theological Seminary, she chaired the General Convention’s Committee on the State of the Church from 2015 to 2018, and she served on the Board of Trustees of the Episcopal Divinity School, 2013-2016. She is also a published author, editor, and podcaster.

Winnie’s parents immigrated to the United States from India, and Winnie spent part of her early childhood years there. She attended Agnes Scott College in Decatur, GA and earned her bachelor’s degree from Southern Methodist University in Dallas. She then attended Union Theological Seminary and graduated with her Master of Divinity degree in 1999. She was ordained to the deaconate in Los Angeles in 1999 and to the priesthood six months later in 2000.

“I think what drew me to Pauli Murray is that she created a reality that was true to her lived experience in her body. She didn’t deny the things that she held true, even when they didn’t align with the movements of the time. I just feel a really deep resonance with that. I feel called to serve the church, a church that didn’t know what to make of me through most of my life.”

Barbara Lau: Recently, someone who knew Pauli Murray shared that everyone who knows Pauli has a “Pauli story.” What’s your Pauli story?

Rev. Winnie Varghese: I have so many stories people have shared about Pauli Murray, so I'll tell you one. When I was the rector of St. Mark's Church-in-the-Bowery, which is in the East Village [in New York City], a man came to visit me who wanted us to bury the ashes of his mother on site. Now the scandal is that it's the East Village in Manhattan so you can imagine there's very limited space to bury anyone. Somehow he had figured out that we're one of the few places that still had a crypt that could open, and you could put ashes in it. Very few people are buried there because there is very limited space.

So he comes to ask me this, and so we're trying to figure out what to do, right? I like him a lot and he says, “My mother has lived in this neighborhood forever. When I came out as a gay man she was really supportive. She was part of the Harlem Renaissance, and knew all of these amazing characters who were part of my growing up.” She sounds wonderful.

He looks at me and says, “Have you heard of Pauli Murray?”

“Yeah I’ve heard of Pauli Murray.”

He says, “My mother was the house mother at one of the women's dorms at Howard. The Dean of the Law School - the man that organized the law school to study what became the critical move of civil rights and shifted the nature of how we understand our constitution, he intentionally recruited people like Thurgood Marshall and others to come together to figure this out.

Pauli Murray applies to Howard and she's admitted. That dean of the Law School goes to this man's mother and, according to him, says, “We've admitted this woman and she would have to live here. She lives a questionable lifestyle, and if you say no, and there's nowhere for her to live then we don't have to admit her and that's fine. You can say no.” So she said, “Yes, why not? I don’t know what the problem is.”

Of course, we buried his mother. It made me wonder how many people, for all of us, no matter how fierce and mighty we are, are also equipping and empowering.

I told that story to a gathering of leaders at St. Mark’s. As I’m telling the story, this older Black woman who has been there forever, said, “Oh, yeah. Pauli Murray was a member of the church. She was the first woman on the vestry. She wrote some really heated letters - I'm sure they're in a file. She was the first woman, and she was so angry with a lot of what we were doing. We were all separatists then, there was a Black and brown caucus. She was so enraged by it that she wasn't very pleasant to be around, and then she quit out of frustration by how horrible the men on this vestry were.” Someone brought me the Pauli Murray file. That's my Pauli Murray story.

BL: Where did you first learn about Pauli Murray?

WV: I've been trying to think about this and I don't know. As long as I can remember, I have had a picture of Pauli Murray on my desk from when I was in seminary.

I think of all the different ways I might have encountered her - I think what happened is I encountered her through her activism and not through the Episcopal Church. Then I saw a picture of her with a collar on and was so moved by it that I just kept it. That was before the Internet was really a thing, so I got Proud Shoes and I got some articles and she was kind of a personal mentor to me in my mind.

I know I didn't learn about her in seminary. I think it was just my own digging around, and then, when I came back to New York, started to understand that I was living in spaces that she had been in, and then began to learn from people who knew her personally.

BL: How is the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray an inspiration for your ministry?

WV: I just learned, a couple of years ago, that we share an ordination date. She was ordained on January 8th. I had no idea.

As a young adult, I assumed that I would have a life as an activist and would be fairly on the margins of things. My sense of what is right tends to be a little bit on the radical side. She, like Dorothy Day and others, I find her story so inspiring.

What was inspiring was I didn't understand the faith component of her life until a little bit later in my own life. I was really moved by her vision for what is right that is so internally driven in a world where segregation was the way of the land. Fighting segregation was about defining oneself as purely Black or white. Feminism was white. Poverty and illness were defining. She wasn't defined by any of those categories for me was so true to my life.

If I wanted to exist in this country, people like me didn't exist. In my young mind, I could disappear. When I would ask professors about it, to try to understand where I fit as an Indian woman, as a queer woman, and at that time not necessarily looking like the gender people expected me to look like - imagining a future with a vocation in the church? Those things literally didn't exist.

I think what drew me to Pauli Murray is that she created a reality that was true to her lived experience in her body. She didn't deny the things that she held true, even when they didn't align with the movements of the time. I just feel a really deep resonance with that. I feel called to serve the church, a church that didn't know what to make of me through most of my life.

Pauli Murray walks through categories that we still struggle with. To me, so inspiring and so brilliant. The emotional and intellectual capacity to produce what she produced? And to stay alive? And to be true to all of these identity pieces? Her belief that the system should work for her, that systems can work for her, that she would force them to work. It’s so profoundly inspiring.

BL: So I noticed that you use she/her pronouns, and that Pauli Murray pushes us to think more in a more complicated way about gender and gender fluidity. I just wonder, as a member of the LGBTQ+ community, how do you see Pauli inviting us into a deeper conversation?

WV: I think one of the remarkable things to watch in Pauli Murray’s legacy is how many communities deeply identify with some part of her story. She is able to tell her story in such a way, and live her life in such a way that in 2022, fifteen-year-olds are still identifying with that story in ways that, frankly, Pauli Murray couldn't have imagined.

I think the right way to talk about Pauli Murray is without pronouns - the right way to talk about many things is without pronouns. I apologize for my own inaccuracy.

Queerness is much bigger than my expression of queerness. Pauli Murray invites us to some humility in our identities. If the world doesn't like the version you are or says that who you are should look a different way - I feel like Pauli Murray didn't do that. Pauli Murray plays with identity, tests it, shifts.

Again, such admiration, for forcing doctors to be better than they were, and medicine to be better than it was.

BL: What is inspiring your Sermon that you're going to be offering here in Durham?

WV: I find that for Pauli Murray in particular, Pauli Murray will inspire that sermon.

I have no doubt in my mind that I will hear something so resonant with this time and this particular political crisis and crises around liberation. I think I’m one of the millions that feels like Pauli Murray speaks to me directly. I'm really grateful to have this opportunity to come to St. Titus - it's an opportunity to refresh my reading and my listening. I’m really, really honored

BL: We look forward to your ideas about what Pauli Murray is calling us to do today, and we can't wait to host you in Durham. Thank you so much.