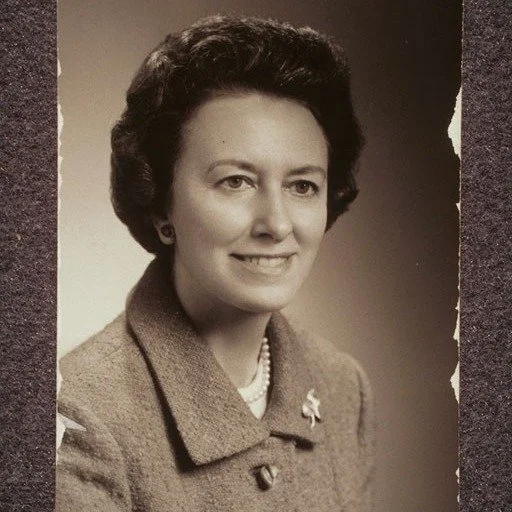

Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University

Who is the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray?

The Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray was a twentieth-century human rights activist, legal scholar, author, labor organizer, poet, Episcopal priest, multiracial Black, LGBTQ+ Durhamite who lived one of the most remarkable lives of the 20th century. S/he was the first Black person to earn a JSD (Doctor of the Science of Law) degree from Yale Law School, a founder of the National Organization for Women and the first Black person perceived as a woman to be ordained an Episcopal priest.

Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University

Pauli Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland on November 20, 1910, the fourth of six children to nurse Agnes Fitzgerald and educator William Murray. Agnes Fitzgerald Murray died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1914. William suffered from depression exacerbated by the long-term effects of typhoid fever and was eventually confined to Crownsville State Hospital where he was later murdered by a white guard in 1923.

After Agnes’ death, Murray was sent to live with their* aunt, Pauline Fitzgerald Dame, and their grandparents, Robert George and Cornelia Smith Fitzgerald, in Durham, North Carolina.

After graduating from Hillside High School in 1926 with a certificate of distinction, Murray moved to New York City. S/he attended Hunter College and financed their studies with various jobs, ultimately graduating in 1933 with a degree in English Literature. S/he changed their birth name to “Pauli.” Throughout the 1930s, Murray actively questioned his gender and sex. He repeatedly asked physicians for hormone therapy and exploratory surgery to investigate his reproductive organs, but he was denied gender-affirming medical care.

At the same time, Murray worked for the Works Projects Administration (WPA) and as a teacher at the New York City Remedial Reading Project. S/he wrote fervently; Murray’s articles and poems were published in various magazines including Common Sense and The Crisis, a publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Murray quickly became involved in the civil rights movement. In 1938, s/he began a media and letter-writing campaign to enter graduate school at the all-white University of North Carolina. Despite a lack of support from the NAACP, Murray’s campaign received national publicity. During this campaign, Murray developed a life-long friendship and correspondence with the first lady at the time, Eleanor Roosevelt.

Article in Durham's Carolina Times, April 6, 1940 titled “Jim-Crow Bus Dispute Leads to Girls’ Arrest.” Excerpt describes the arrest of Pauli Murray and friend Adelene McBean.

A member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Murray worked to end segregation on public transport. In March 1940, s/he was arrested and imprisoned for refusing to sit at the back of a bus in Virginia. In 1941, Murray enrolled at the law school at Howard University with the intention of becoming a civil rights lawyer. The following year s/he joined George Houser, James Farmer, and Bayard Rustin to form the nonviolence-focused Congress of Racial Equality.

Pauli Murray’s writing continued to influence and shift the movement for justice. In 1943, Murray published two important essays on civil rights: “Negroes Are Fed Up” in Common Sense, and an article about the Harlem race riot in the socialist newspaper, New York Call. Their most famous poem, Dark Testament, was also written in that year. The poem was published as a part of a larger collection of his work in 1970 by Silvermine Press, which was republished in 2018 by W.W. Norton as Dark Testament and Other Poems.

Class of 1944, School of Law, Howard University. Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University.

In 1944, Pauli Murray graduated at the top of their law school class from Howard University. It was at Howard that s/he also became acutely aware of the oppression s/he faced as a Black person perceived as a woman, coining the term “Jane Crow,” to describe their experience. The Rosenwald Fellowship was awarded to the valedictorian, and previous top graduates had used the fellowship to attend Harvard University. Despite winning the fellowship, Murray was rejected from Harvard Law School due to sexism - echoing previous rejections that Murray experienced. Instead, Murray went to the University of California Boalt School of Law where s/he received an LLM (Master of Laws) degree. Their master’s thesis was titled The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment.

After graduation, Murray returned to New York City and provided support to the growing civil rights movement. Their book, States’ Laws on Race and Color, was published in 1951 thanks to the United Methodist Women who commissioned this work as a service to the movement and part of their Charters for Racial Justice. Thurgood Marshall, head of the legal department at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), described the book as the “Bible” for civil rights litigators.

In the early 1950s, Murray, like many Black citizens involved in the civil rights movement, was suppressed by McCarthyism. In 1952, s/he lost a US State Department post at Cornell University because the people who had supplied her references (Eleanor Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall, and A. Philip Randolph) were considered “too radical.” S/he was told in a letter that they decided to give “one hundred per cent protection” to the university “in view of the troublous times in which we live.”

Pauli Murray presents a copy of Proud Shoes to Lloyd K. Garrison, former president of the National Urban League (1956). Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University.

In 1956, Murray published Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family, a biography of how white supremacy and anti-Blackness oppressed their grandparents and their efforts of racial uplift, and a poignant portrayal of their hometown of Durham. Shortly after the book came out, Murray was offered a job in the litigation department at a new law firm, Paul, Weiss, Rifkin, Wharton, and Garrison. While working there, Murray met their partner Irene Barlow, the office manager at the firm.

In 1960, Murray traveled to Ghana to explore their African cultural roots and teach law. While there, s/he co-authored a book, The Constitution and Government of Ghana, with Leslie Rubin. When Murray returned, s/he enrolled at Yale Law School where s/he studied for the JSD degree and mentored several young women activists, including Marian Wright Edelman, Eleanor Holmes Norton, and Patricia Roberts Harris who all became leaders in their own right.

President John F. Kennedy appointed Pauli Murray to the Committee on Civil and Political Rights as a part of his Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. In the early 1960s, Murray worked closely with A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King but was critical of the way that men dominated the leadership of these civil rights organizations. In August 1963, s/he wrote to Randolph and asserted that s/he had “been increasingly perturbed over the blatant disparity between the major role which Negro women have played and are playing in the crucial grass-roots levels of our struggle and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned in the national policy-making decisions.”

Pauli Murray joined Betty Friedan and others to found the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966, but later moved away from a leading role because s/he did not believe that NOW appropriately addressed the issues of Black and working-class women.

From 1968 to 1973, Dr. Pauli Murray served as a faculty member at Brandeis University teaching an early American Studies program. In 1973, following the death of their longtime partner Irene Barlow, Murray left their tenured position to become a candidate for ordination at General Theological Seminary.

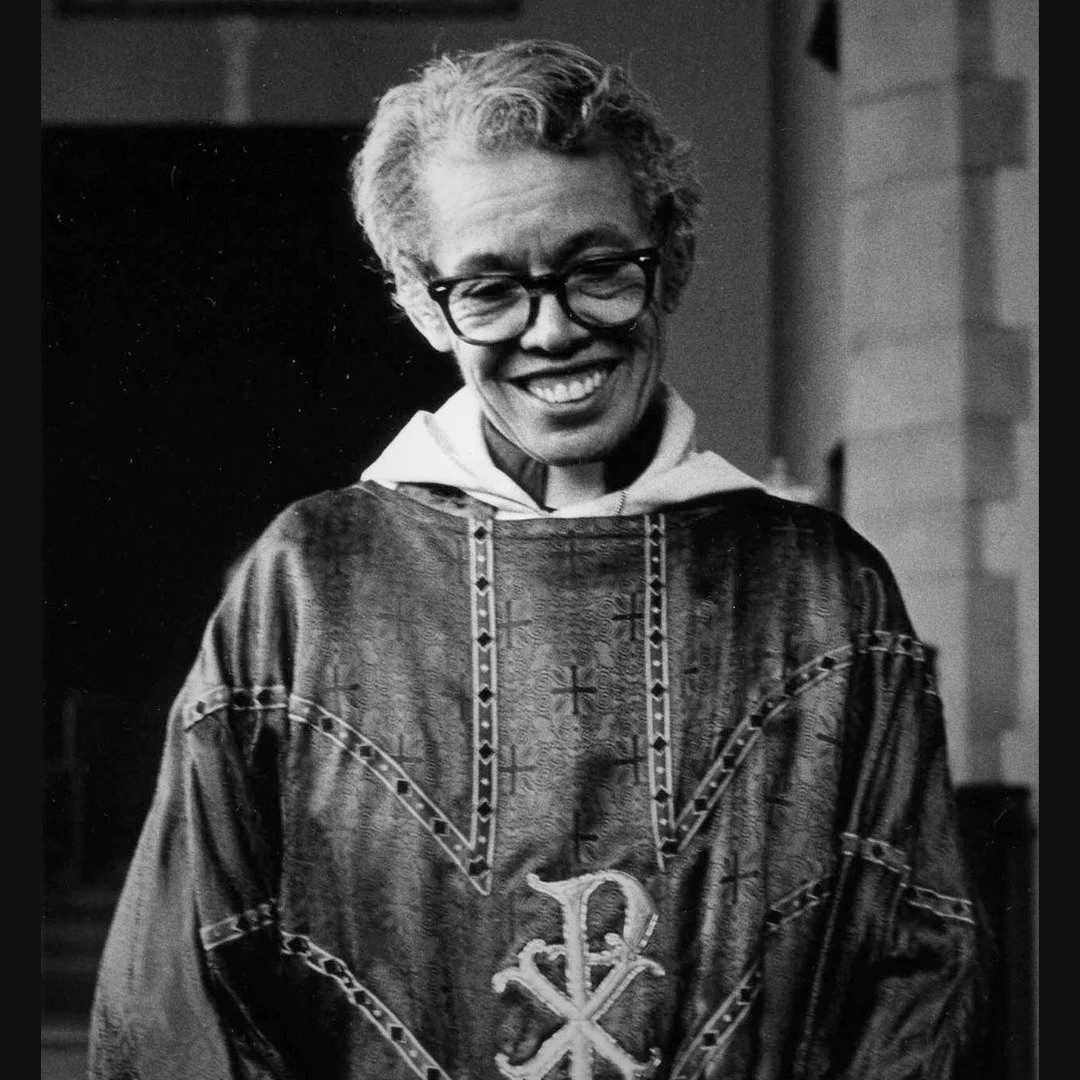

Pauli Murray’s ordination (1977). Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University.

In 1977, Pauli Murray became the first Black person perceived as a woman in the U.S. to become an Episcopal priest.

Pauli Murray died of cancer in Pittsburgh on July 1, 1985. Their autobiography, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage, was published posthumously in 1987. The book was re-released as Pauli Murray: The Autobiography of a Black Activist, Feminist, Lawyer, Priest and Poet in 1987, and was republished under its original title with a new introduction by Patricia Bell-Scott in 2018.

Their book of poetry, Dark Testament and Other Poems with a new introduction by Elizabeth Alexander, originally published in 1970 has also, like the autobiography, been reissued by Liveright Publishing, an imprint of W.W. Norton. Perhaps Murray’s most recognized work, Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family, has been in print since its original publication in 1956.

Since their death, additional books have been published about Murray’s life and work, which can be found on our Resources About Pauli Murray page.

*Learn about our use of pronouns here.